Do we need black people on our banknotes? – The Guardian

Do we need black people on our banknotes? The Guardian

source

The Guardian, Fri 7 Jun 2019

I hesitated before supporting the campaign for representation. However, the Bank of England’s weak response convinced me that the campaign is necessary.

Backing Representation Campaigns

Usually, I enthusiastically support new campaigns that address Britain’s failure to recognize Black contributions in building modern Britain. For example, I have backed critiques of statues that glorify white supremacists while ignoring people of color. I have also supported efforts to reform the curriculum, which often overlooks the racialized nature of British history. I understand the need for a museum of empire and appreciate books like Washington Black, which tells the fictional story of a Black inventor erased from historical records.

Hesitation Over the £50 Banknote Petition

When asked to sign the petition calling for a Black person to appear on the new £50 banknote—a decision the Bank of England was expected to announce this summer—I hesitated. This hesitation was not because I doubted the strength of the argument. Since 1970, the Bank of England has issued 24 banknotes featuring notable people. All have been white, and only three have been women. Jane Austen, the last woman featured, was added only after a widespread social media campaign and the threat of legal action.

The Case for Banknotes of Color

The campaign for banknotes featuring Black and ethnic minority figures makes a strong case. Black and ethnic minority people have lived in Britain for millennia, yet society has systematically overlooked their contributions. Olaudah Equiano, born into slavery, campaigned passionately for abolition, but his efforts have been overshadowed by the preferred memory of William Wilberforce. Efforts to introduce Mary Seacole, the Black nurse of the Crimean War, still face criticism as a “PC myth” in favor of her contemporary Florence Nightingale, whose controversies are rarely mentioned. For centuries, Britain regarded black people as inferior. Those who gained recognition had to be exceptionally remarkable to overcome the stacked odds.

Whose History Does the Money Reflect?

The question is not whether Black people deserve to appear on money, but whether the money truly deserves us.

In the US, Harriet Tubman the giant of the Underground Railroad—was announced as the face of the new $20 note. She became the first woman and African American to appear on the currency. However, some expressed unease about placing the image of a formerly enslaved woman on money. This discomfort reflects a distrust of American capitalism, which has yet to acknowledge or atone for its ongoing sins against black citizens. Is it truly progressive to honor those who rebelled against slavery on the very currency that symbolizes the system they fought?

Racism, capitalism and historical exploitation

The connection between racism and capitalism is well documented. Philosophers like Hegel and Nietzsche recognized how exploitation of so-called inferior people fueled European growth. Hegel stated that a “civilized nation” believes the rights of “barbarians” are unequal and treats their autonomy as mere formality. In the UK, the Bank of England both emerged from and oversaw a system that commodified Black people, driving Britain’s economic growth. Four Bank of England governors and directors owned slaves, slave ships, plantations, or led the Society of West India Merchants, which protected those interests. After slavery stole Black bodies, the empire stole their land.

Acknowledging History Within Our Systems

We must relentlessly acknowledge this history as long as we still use the system built on it. I joined 150,000 others in supporting the Banknotes of Colour campaign. The campaign’s importance became clear from the Bank of England’s response. Unlike Canada and New Zealand, which feature ethnic minority figures on their currency, the Bank avoided addressing the request for a new £50 note. Instead, it shifted the focus to recognising “military service” and “science,” both already featured on existing banknotes.

Institutional Resistance to Change

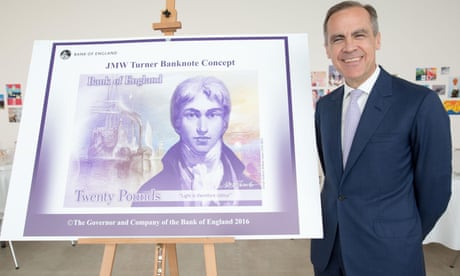

Like many British institutions, the Bank of England talks about diversity but often fails to act. I have spoken there myself. The governor, Mark Carney, and other leaders nodded earnestly at my words about history and racial identity. Yet the Bank seems to echo President Trump’s stance, delaying the new Harriet Tubman $20 bills initially planned for 2020 until 2028. This delay feels like kicking the issue into the long grass.

Conclusion: The Symbolism of Representation

Including Black figures on banknotes cannot solve racial injustice. However, refusing to include them powerfully shows how little many institutions care..